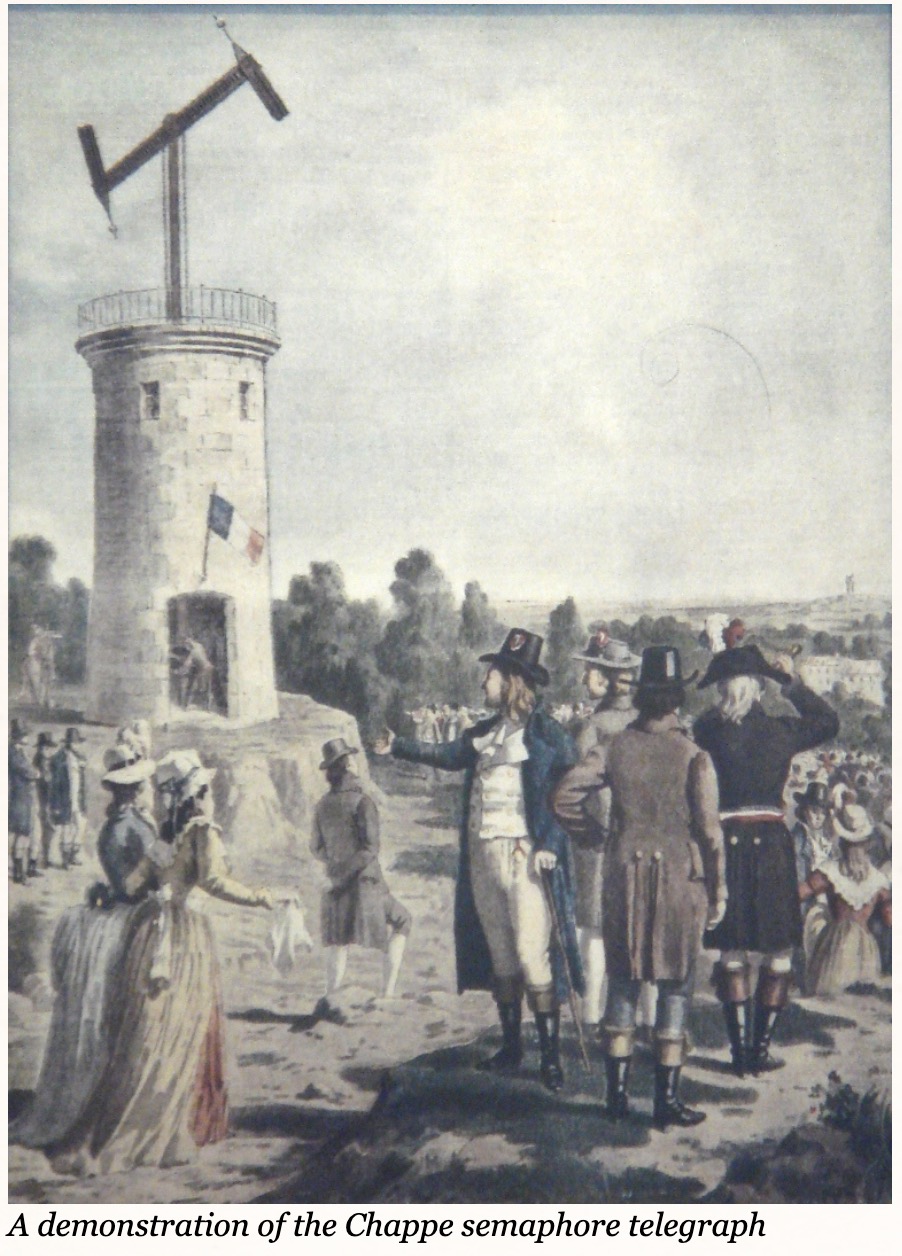

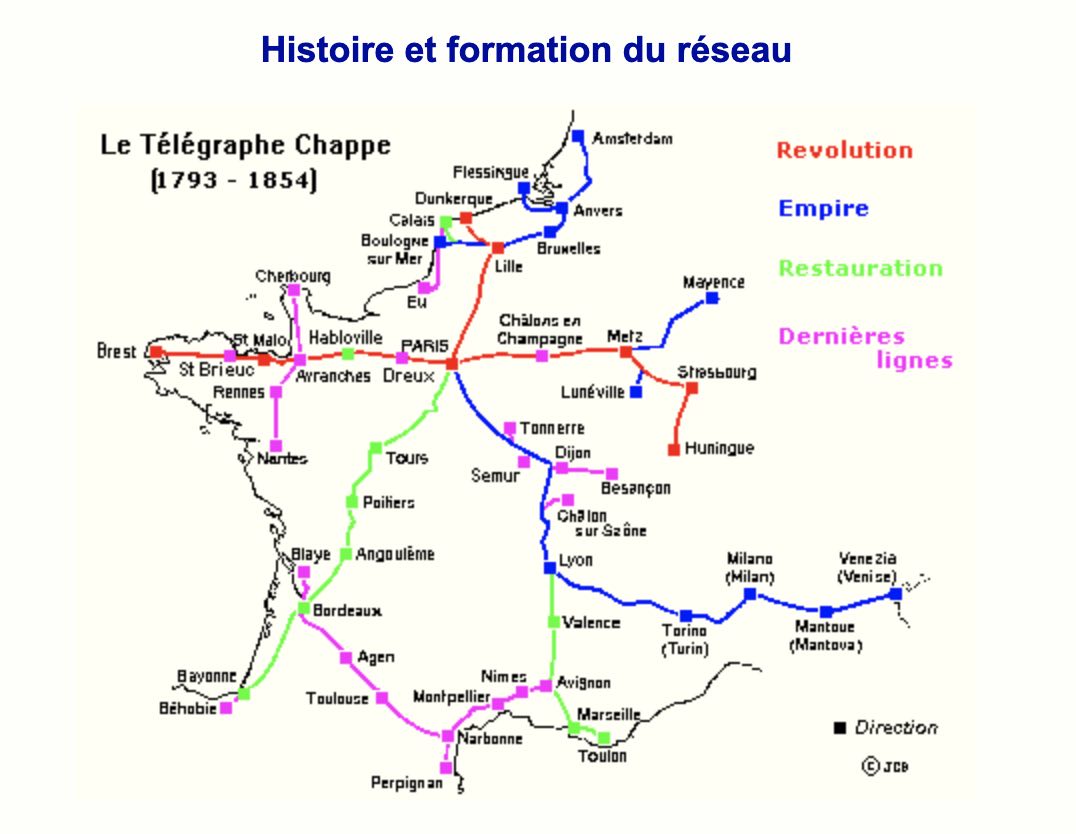

I’ve been thinking about the telegraph a lot lately. Did you know that long before there was an electrical telegraph of Morse Code fame, there was a visual telegraph? It was invented by a monk in France names Claude Chappe. Napoleon used it during his wars. Signal stations were spaced 10-15 Km apart and were observed by someone with a telescope. The codes were written down and re-transmitted to the next station, to be decoded there.

Chappe’s system reminds me of the opening of Aeschylus’s Orestia, where Clytemenaestra knows that her husband is finally returning from the Trojan War because of a system of beacons:

Clytemnestra: Hephaestus, sending forth a bright blaze from Mount Ida, and then, from that courier-fire, beacon sent on beacon all the way here. Ida sent it to Hermes’ crag on Lemnos, and thirdly, from the island, the steep height of Zeus at Athos received the great torch. Then, the mighty travelling torch in all its delight shot up aloft to arch over the sea, and the pinewood, like another sun, conveyed its message in light of golden brilliance to the watch-heights of Macistus. (from Brian Le’s Blog)

Chappe’s system was in use for over sixty years. It was eventually superseded by the electrical telegraph that those of us of a certain age still remember. It remained in use until the digital era and email superseded it. One of its most dramatic moments was laying cable across the Atlantic. You can read about those efforts here.

A few months ago I made friends with author Ceridwen Hall. We share a passion for the history of early technologies, including the telegraph. Ceridwen has written poems, stories, and articles about telegraphy: what it felt like to use one, who worked as telegraph operators (often women). Here is a sample of her work:

Network

Ceridwen Hall

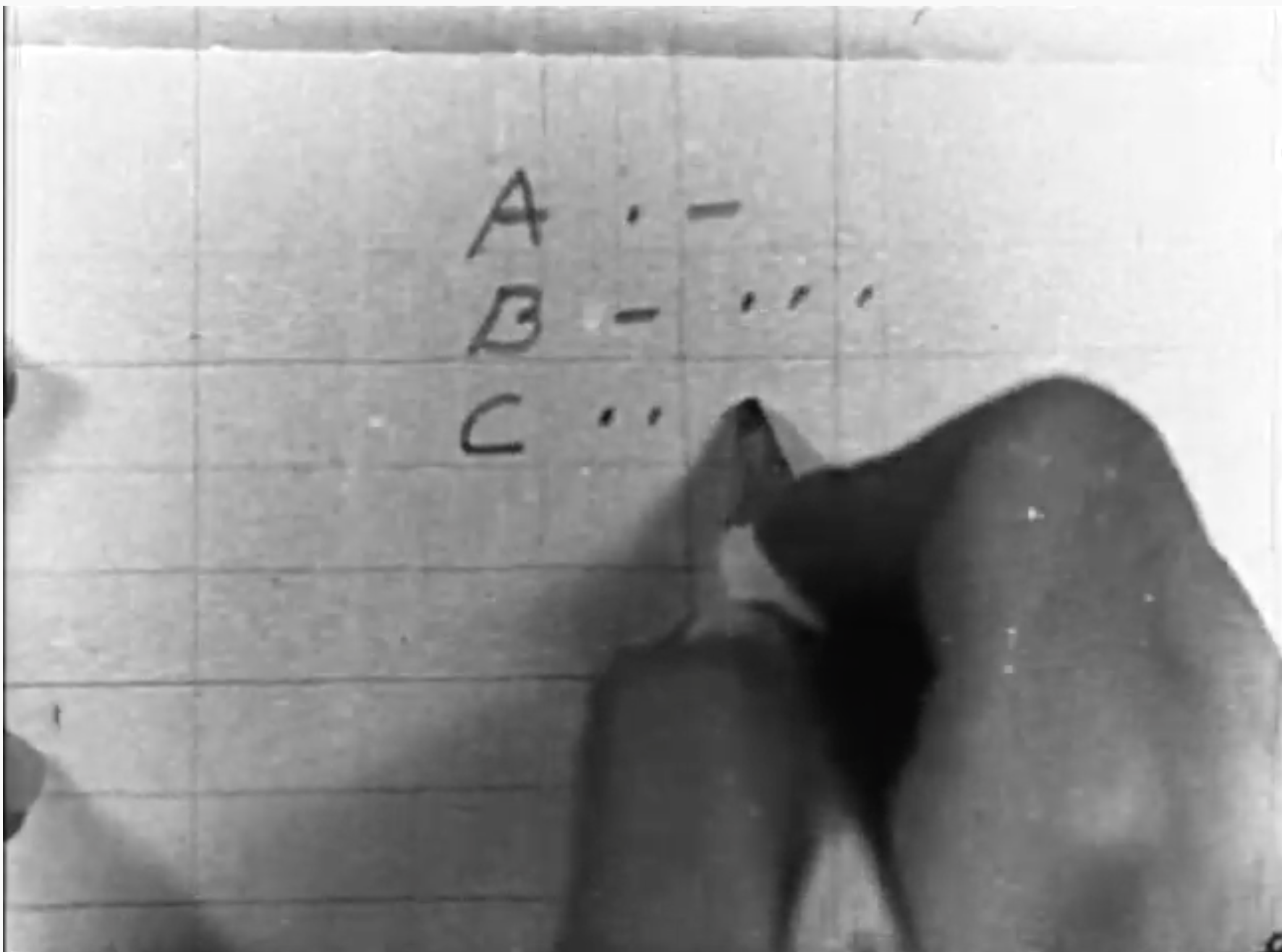

always on-line

a telegraph operator might be permitted or obligated to fill her spare minutes with various kinds of needlework.1 And possibly other domestic tasks, if the wire ran directly through her home. While it involved the mysterious force of electricity2 and a certain intimacy with the words of strangers, telegraphy was viewed as suitable work for women because it could be done while seated and would therefore not put too great a strain on their reproductive organs. Though not as well recognized as technical skill and transmission speed, tidy handwriting and polite manners were essential traits in this nascent customer service industry. Here in Utah, young women were among the first trained telegraphers; three friends, who chose the wire pseudonyms Belle, Estelle, and Lizette from their favorite novel, learned Morse code by tapping out newspapers on a wooden practice key. Subsequent telegraphic work and their marriages took them to separate towns, but they kept in frequent electronic contact throughout their lives, even stringing a private telegraph system between their homes so that their daughters could learn to operate

You can read the full poem here.

I was still reading about telegraphs when I discovered, to my joy, that the New Hampshire Telephone Museum in Warner had a display about the relationship between telegraphs and trains. The exhibit is up until the end of October, 2021. Here is the description from their website:

As the railroad system expanded, so did the need for a reliable method of communicating. The New Hampshire Telephone Museum’s 2021 special exhibit explores the history of railroad communications as it evolved from a system of simple signs to the use of the telegraph and then the telephone.

In addition to the communications methods they utilized, this exhibit delves into the use of the railroad to carry another form of communication – the U.S. Mail – a system which, coincidentally, was perfected by the future president of the Bell Telephone System, Theodore Vail.

In keeping with the communications theme, the exhibit is rounded out by a fun look at the words and phrases of today whose roots stem from the days of the railroad.

If you can’t make it to Warner, NH, you can read about it here.

Jeff Rapsis, who plays live music for over one hundred silent film events a year, presented and played at the Warner Town Hall last night. The program was called "Stop! Look! Railroad Melodramas!"

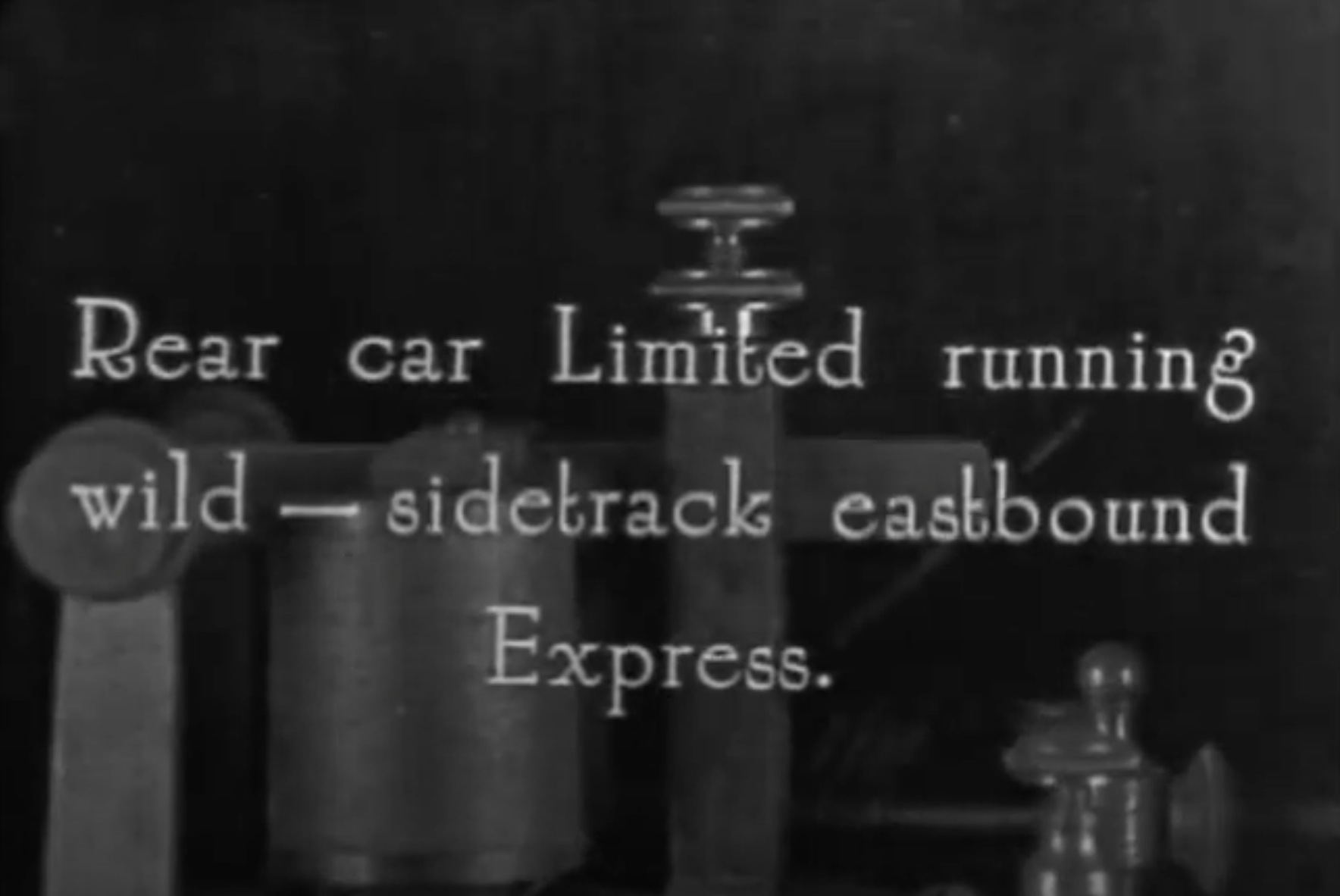

The films were two one-hour thrilling melodramas from the 1920s that vividly depict the relationship between trains and telegraphs.

In 'The West-Bound Limited' (1923), a fired employee takes revenge on the railroad by setting a trap for a head on collision between a passenger train and a freight train. The hero works in the station depot as a telegrapher:

In 'Transcontinental Limited' (1926), Jerry Reynolds is an aging train engineer fast approaching retirement, but his eyes are giving out even faster! Will he still collect his pension? The films features thieves with a conscience and a thrilling ride at the end on a train car that is out of control and speeding down a mountain!

This film is a great illustration of the role telegraphs played in train operation.

The Rails West website talks about how telegraphs were used in train operation:

First use of a telegraph to direct train operation

In 1851 Charles Minot, Superintendent of the Erie, used a recently installed telegraph line to issue the first train order, a message changing the meeting point between two trains. To make this work safely, Minot needed a confirmation that the train being held at the new meeting point had "gotten the word." This alteration to the timetable allowed more efficient movement.

The record of the very first train order sent in the U.S. was documented by Edward H. Mott in his book on the history of the Erie Railroad, Between the Ocean and the Lakes. According to William H. Stewart, a retired Erie Railroad conductor, in the "fall of 1851," Charles Minot was on a west bound train stopped at Turner, N. Y. waiting for an east bound train coming from Goshen, N. Y., fourteen miles to the west. The impatient Minot telegraphed Goshen to see if the train had left yet. Upon receiving a reply of "no," Minot wrote out the order: "To Agent and Operator at Goshen: Hold the train for further orders, signed, Charles Minot, Superintendent." Minot then gave Stewart, who was the conductor of Minot's train, a written order to be handed to the engineer: "Run to Goshen regardless of opposing train." The engineer, Isaac Lewis, refused Minot's order because it violated the time interval system. Minot proceeded to verbally direct Lewis to move the train but he again refused. Lewis then became a passenger on the rear seat of the rear car and Minot, who had experience as an engineer, took control of the train and proceeded safely to Goshen. Shortly thereafter, the Erie adopted the train order for the movement of its trains and within a few years the telegraph was adopted by railroads throughout the U.S

In the Transcontinental Limited, the telegraph gives the train orders, but then the hero picks up a telephone to make local calls for help. This symbiotic relationship between telephone and telegraph continued until the two were blended in email and social media in our digital era.

Ceridwen Hall has written a poetic view on this too:

INSTRUMENTS

Souilly, France 1918

Cables stretch through barbed wire and battlefields

become switchboards. From above, pilots report,

invisible hands seem to manipulate the plugs

in thousands of electric flashes. Generals speak

to every trench as Signal Corps women connect

hundreds of calls. They breathe smoke and speak

by Ceridwen Hall

Beacons, Semaphores, Telegraphs: the biggest push in their development were usually associated with war. Along with mail, email, and social media, these are the networks that connect us. These films from the 1920s show us how things, show us things that have all but disappeared.

If you are in New Hampshire, you can download a self-guided tour of sites important to rail history for the area around the museum.

Sources

The Rise and Fall of the Visual Telegraph blog by Parisian Fields

A Brief History of the Optical Telegraph by Ai Sin Chan XOXOZO Blog

Networks (poem) by Ceridwen Hall

First failed transatlantic telegraph

Jeff Rapsis Film Screening Schedule

Transcontinental Limited (1926)

Telephone railroad communication exhibit